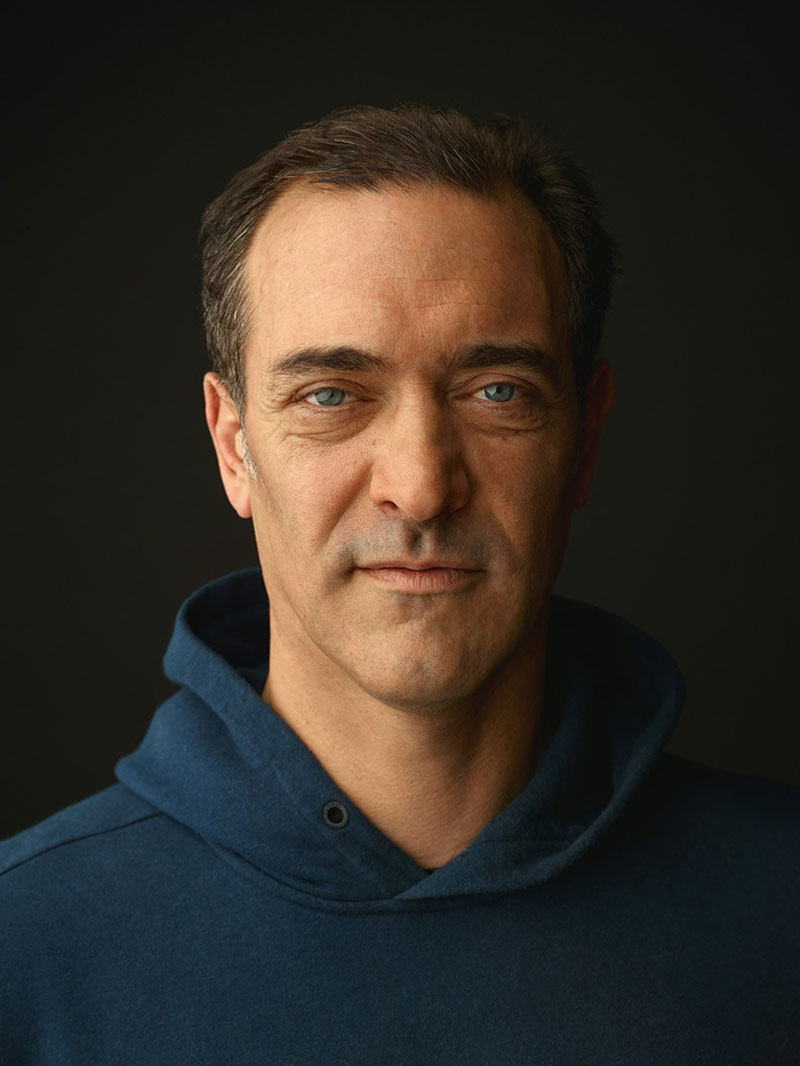

Dr. Steven Waterhouse aka “Seven”

CEO of Orchid Labs, Inc.

The Importance of Data Privacy with Orchid Founder Seven

Orchid Labs’ VPN is Decentralized, and Not Just with Blockchain

Introduction: Dr. Steven Waterhouse (aka Seven), founder of Orchid Labs, speaks with me in this podcast about the importance of data privacy. It’s timely, as two relevant announcements were made today, July 19, 2021. First, for the first time in the history of the organization, NATO countries are coming together to accuse China of cyberattacks via Microsoft’s Exchange Server, as reported by Wired, Axios and others:

https://www.wired.com/story/china-hacking-reckless-new-phase/

https://www.axios.com/china-cyberattacks-nato-181e71d2-7414-45f3-9463-c8b1d46392c1.html

Second, The Guardian has released their special investigation of Pegasus, spyware created by NSO Group Technologies (named for founders Niv Carmi, Shalev Hulio and Omri Lavie; only one of many companies doing this) that governments around the world use to spy on anyone who uses an internet-dependent phone. Political families and journalists around the world who are being spied upon are calling foul.

Edward Snowden, who spoke at Dr. Waterhouse’s Priv8, Orchid Labs’ digital privacy summit March 23-25, 2021, stated to The Guardian that spyware should not be commercially available. It is taking over phones completely. There is no privacy at all for victims, and this invasion of privacy can happen to anyone. You could be flagged as a ‘person of interest’ for ‘liking’ certain social media posts. With automation, AI, and other emerging technology, the computer algorithms are all applied automatically, so they can invade millions of phones at once, then report content automatically as well. All of this has been happening for a long time, and now we have the evidence:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jul/19/nso-clients-spying-disclosures-prompt-political-rows-across-world

The future of democracy is threatened, our own right to privacy is not being honored, and we don’t even have the right to control who sees our data, and where it ends up. These issues were also covered a few years ago in the epic report by The Guardian, that Cambridge Analytica was manipulating elections using social media feeds that included fake news, which was featured in the Netflix documentary, The Great Hack.

So you see the importance of having ethics in AI from the start, because five years down the road, it will be too late. If the algorithms are done responsibly now, many problems will be avoided in the future.

Do you need more info?

- Matthew Bailey addresses these issues in his book, Inventing World 3.0; Evolutionary Ethics for AI.

- I interviewed Matthew for our podcast when the book was released here.

- I interviewed Will Griffin, Chief Ethics Officer of HyperGiant, here.

- Protopia AI is providing ways for AI companies to address these ethical issues.

- On this page is our new interview with Dr. Steven Waterhouse of Orchid Labs focusing on data privacy and using the blockchain for VPNs.

– Myrna James Yoo

Myrna:Thanks for joining us today, Seven. We are excited to discuss Orchid Labs, your VPN (Virtual Private Network, which hides the user’s IP address by changing the indicator of their physical location), and issues around digital privacy. I know that Edward Snowden recently spoke at your Data Privacy Summit, and you spoke at Collision, the innovative tech conference, which incidentally I attended a few years ago. Tell us about Orchid.

Seven: Orchid is a company that focuses on digital privacy. We have a suite of tools, including our VPN client, that allow you to connect to a decentralized network of VPN providers. Why this is interesting is that you’re able to route your traffic between different providers and hide information about who you are and where you’re going.

We believe that digital privacy is a right that we should be focusing on protecting, just like all privacy should be a right. And we’ve been working on this now for a number of years. The technology behind it is based on cryptocurrency and blockchain. The providers and the network are paid using different kinds of cryptocurrency. Our team is composed of some real experts in network security, digital privacy and open-source technology. We are based globally, with a bunch of our team in the United States and I’m in Europe. We even have teams in Japan and all over the world.

“If you can decouple those two pieces of information (identifying info such as IP or payment info and destination on the internet), then you’ve essentially formed a new level of privacy.”

Myrna: Great. Thank you. I understand that it’s based on blockchain technology, which is a new, very secure technology, I won’t go into the definition of that. But do people need to use cryptocurrency in order to pay to use Orchid as their VPN?

Seven: I think anybody who watched Saturday Night Live on May 8 will know a little bit about cryptocurrency after the doge-father, Elon Musk, gave his introduction. People tend to get confused around the idea that you can separate these two ideas of blockchain and cryptocurrencies. Why should we have new currencies because we already have the nice U.S. Dollar, Euros and other global currencies?

The thing that we innovated around is, in addition to being able to use good old cryptocurrencies, our platform can accept traditional payment as well. I’ve been in this space since 2013, so I’m very deep into this thing, I’m kind of a native now. But we also realize that that can be kind of complicated, to go get some Orchid tokens, so now we also accept any other currency.

That can be kind of complicated, especially if you’re just using a mobile application, which a lot of us do when we’re using VPN. We say, “Hey, I’ll connect to a hotel wifi or conference wifi, maybe I should secure this because this wifi is really not that secure.” Or I am in Mexico and I’ve got an HBO subscription, but I really want to watch HBO and I can’t do it because HBO says when you’re in Mexico, you can’t watch it. So, I’m going to pretend I’m in the United States using a VPN.

Also, we enable you to buy a little bit of VPN usage, literally pay as you go. Rather than a subscription, you can just buy a little bit. And you can do that using your tools on Apple or, actually quite soon, Android will be releasing this feature also, using in-app payments, which is the same kind of thing you use when you buy something in a game on your phone or buy the professional version of an application. And with Orchid, you can get started for as little as a dollar now. We’ve been innovating very hard in that payment space and trying to make things very easy for people to just connect without having to understand how the actual system works.

Myrna: Awesome. That’s great. People need to know that they should have a VPN. It’s the most basic layer of privacy that they can put on their laptops and phones, right?

Seven: Yes, and I think the thing to think about there is, you have to think about your risks, right? So, we do a lot of work on our team talking about privacy or security and the like. It’s kind of a layered system. So, it depends on who you are and what you think your risks are. So, if you’re a person who speaks out against the government, and that government doesn’t really like the fact that you speak out against them, and the risk for doing so could be very severe, like physically severe for you, then you need to think very carefully about all the tools you’re using, of which our tool is just one.

Now, if you’re just in Mexico and you want to watch HBO, then you have a different kind of risk. The risk is, does HBO find out that you’re actually in Mexico and they don’t really like it. You have to kind of think through these risk levels. And then what Orchid does is it provides a very good tool, which we believe is better than just using a simple, plain old VPN.

And the reason for that is that when you’re using a VPN service, it encrypts and tunnels your traffic, or takes your traffic, and puts it through a VPN server. And remember, when we talk about the cloud and servers, these things are just run by people; they’re just people running machines somewhere. So, someone else is then taking the traffic, encrypting it, sending it to the website that you’re looking for, getting the result back, and sending it back to you all encrypted. So, you feel safe.

Well, you’re as safe as the person who you’re sending that data to. There’s a person running that server, whether it’s one of these main VPN companies (we actually partner with a number of them) but you’re as safe as any one of those companies that you’ve used. Those companies also have your credit card information and address and all the things you need to set up a subscription with them. They actually know a lot about you. One of those companies may become compromised, for example, and we see hacks all the time – people’s data getting leaked. All these things are fairly normal now; we’ve become accustomed to it.

First of all, you don’t need the billing information, you don’t need the credit card. Even if you’re using the in-app payments, that information is not going to the VPN company. And then the other thing you can do is to connect different providers together so that none of the providers know both pieces of information, which is important. The two pieces of information that connect you are information about who you are, such as your IP address or your credit confirmation, and where you’re going – which website you’re going to. If you can decouple those two pieces of information, then you’ve essentially formed a new level of privacy.

Myrna: So, you’re actually innovating in both areas of VPN. There’s the payment side of the VPN, for which you’re using blockchain and cryptocurrencies, but also allowing payment to be done in-app, which makes it easy for people. And you’re also innovating on the way the VPN actually keeps your data private by separating identifying information and internet destination. Also, you’re working with a network of different VPN providers that you trust, right? So, you’re vetting them, making sure that they’re safe.

Seven: Yeah, so we do that. We’re curating the list of VPN providers initially in the network. Now, it’s also open in the sense that other people can run curation service. So, you could say, I know some people who are really good at these things; I trust them. So I’m going to set up a little curator. I’m going to connect that to the Orchid system, and then I could take the Orchid client and change one of the configurations. Let’s say, I want to connect to you to provide space data privacy, or something like that.

And then you could actually have a business model and a relationship with those other groups that you’re connecting to. You could do things like monitor to see whether these people actually adhere to their privacy practices or find out whether or not they’ve had good service levels, and so on. This was never intended to be something that we run. We don’t run any servers. We just provide software to users to download and to providers to use.

It’s very unusual. People in our industry say, “Hey, you know, the VPN service needs to do X, Y, and Z.” But we don’t run the VPN service. And they ask, “Well, who runs it? What do you guys do?” I say, “We provide the software.”

So, the idea is that we want this thing to be fully decentralized so that over time, anyone can run a VPN though bandwidth may be an issue. Arguably, you could do something like that if you had enough bandwidth.

Myrna: That’s amazing.

“The danger here is the cultural hegemony of the FAANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Alphabet’s Google) and the BATs (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) in China. Those things are spreading out to larger parts of the world – automated systems applying culture, value and ethics to groups of people who didn’t sign up for that.”

Seven (09:30): And it’s also a way that you can imagine a different kind of business model emerging. Just to explain a little bit, there’s also a secondary part here, which is that’s we started this whole initiative initially focused on these decentralized VPNs, but really the whole thing was the idea of decentralized services with a privacy component. Now, what does that mean? Well, not to point fingers, but there are very few companies who really run the web today.

People think that means Facebook and Apple and so on. But, no, it’s actually the people behind the scenes. It’s the Amazon Web Services, it’s Microsoft Cloud, it’s Google Cloud. This is actually where the internet is run.

Myrna: Right.

Seven: And these web services are machines and different kinds of configurations. Using something like Amazon Web Services is incredible. You can spin up anything you want really fast and get it running and have services running as soon as you want. It’s incredibly powerful. But a lot of people over time have started to look at the emergence of these sort of centralized points of how the internet is run and say, well, this is interesting.

Myrna: Yes, I am familiar with AWS as a server for geospatial data, and also for their new ground stations that allow for direct download and processing of data from satellites. It’s a game-changer, as you say, on the back end.

Seven: Yes. I’ll get a little political for a minute… so a sitting president can be de-platformed from services just because someone at a company decides that that’s what they’re going to do.

Now, the person in question, his tweets were very interesting over time, and definitely not in my personal flavor, not getting political. But the danger there is this. What if, over time, when someone gets de-platformed, that’s actually someone you like this time round or next time around? What if it’s somebody we’re de-platforming who are trying to fight out in other countries for freedom of expression? In places like China, we already have this firewall situation where huge parts of the internet are not accessible and information like the truth about Tiananmen Square is essentially lost.

So this is one of the big things we’re looking at. Now, VPNs are only one component of that. And the whole idea of being able to decentralize many different kinds of services is something that the Orchid technology and the way we build our payments architecture is very well suited to. So while VPNs are the main component, it’s really kind of like the access layer for these services. And now we have people in the community looking at different ways to explore what else you could do with this kind of technology.

Myrna (12:00): That’s great. As a lifelong member of the press, I really am very concerned about the freedom of speech and the freedom of the press. And so, I agree with you. I’d love to zoom out a little bit now and talk about the whole need for digital privacy in the first place, and data privacy, and how we, as sovereign individuals, should have the right to more control over our lives. That’s sort of how I see this.

And then, can you address ethics? I see data privacy as overlapping with ethics in AI, because with AI and all these algorithms that are out there, no matter what company it is, lots and lots of companies are now claiming to do AI – a lot more than even a couple of years ago.

A lot of them are doing machine learning for predictive analytics. But when it gets into artificial intelligence where the computer takes over, with algorithms and calculations, and they just so easily could run amok as we’ve seen with some of the things that were exposed in The Social Dilemma and The Great Hack and some of those documentaries. So would you just address how ethics in AI overlaps with the need for data privacy?

Seven: Well, an interesting background point is that I did my PhD at Cambridge focusing on speech recognition, but it was also generalized machine learning and specifically what is now called deep learning with some of the algorithms we were working on. When I left and moved out to the West Coast to California, some of the early work I did was with NASA and then also with eBay, Craigslist and Yahoo in the early days of data personalization and machine learning for data. Now, at the time, we didn’t really have data. We sort of had to beg companies for data because there wasn’t any. Now we’re swimming in it, we don’t even know what to do with it. We can go online and find all sorts of ways to access that stuff.

I’m less concerned, at least in the very short term, about things like generalized AI and the machines that can think for themselves. These things are tools, currently. There are arguments to say that we’re on an accelerated curve and guys like Elon Musk talk about the dangers, and I’m a big fan of what they’re doing with open AI so they can open source these technologies.

The thing I think is concerning here, especially with the ethics around these things, is a kind of discrimination based on the way you train systems. I’m exposed to this personally, with the irony of having done my PhD in speech recognition. We built a lot of technologies at Cambridge that went on to become things that we used in Siri and other systems when you talk to United Airlines or all the kinds of things that you have all across the world and the states for that company.

The systems have no idea how to interpret me because I don’t have the right accent. In the UK, I don’t sound UK enough, and in the US, I don’t sound US enough. I’m essentially sort of exposed to an accent discrimination by these machines, which is very strange for an English person because we actually identify people based on their accent as to what class we think they’re in. So, it’s a familiar feeling, but now I have a machine doing it to me.

So that generalizes how people are designing these systems, in a way that is fitting into their culture and ethics that they believe in. So in one part of the world, we’re going to see systems that reflect one set of values. In another part of world, we see systems that reflect another set of values. And so, the danger here is the cultural hegemony of the FAANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google) and the BATs (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) in China.

Those things are spreading out to larger parts of the world – automated systems applying culture, value and ethics to groups of people who didn’t sign up for that. Let’s say you live in New Zealand, right? And you say, I believe these things, I voted my government in, this is what my culture is like and so on. And then you’re using Facebook, but you’re receiving certain curated content, including advertising. Or it could be an app that’s made in Silicon Valley. It could be an app that’s made in Europe, it could be an app that’s made in China or other parts of Asia, which you just like and it becomes popular.

Suddenly, the AI systems that are trained using those cultural values and belief systems now apply to you. So maybe that doesn’t matter for photo sharing as much, though I think it does, because we’ve seen some of the issues there. But when it starts being used in systems that, for example, police our ability to get on flights, police our ability to navigate the world as we know it, and we begin to think that this is normal, then it starts to become much more apparent to us that we are subject to a system that we didn’t sign up for.

Myrna: It’s like the digital discrimination becomes physical real-world discrimination.

Seven: Yeah.

Myrna: And also, this cultural hegemony is creating the social credit scores, such as those happening in China. Are they inevitably coming to the U.S. and the rest of the world? I would say, yes.

Seven (18:00): Yes. And now it’s a social health scores, right. That’s the new thing.

Myrna: Absolutely right.

Seven: I don’t know whether those things are coming – this is like a Black Mirror episode, right? I know there is one that actually talks about this. I think we have to separate these ideas here. We can pontificate about these things as to what’s right or wrong. Hopefully, we live in democratic systems where we’re voting in people to reflect our values. I’m a big fan of coalition government, so it’s not just the people who win the election, but the people who don’t always win the election.

The concern here is that when you’re subject to a system that you didn’t sign up for, that’s something you’re no longer in control of in your life. And those applications that are run by international companies and that are by their nature global, are essentially affecting your ability to do things and live your life in a way that you didn’t choose. And then you end up in the system where you feel like you don’t have a choice because you can opt out of all these social networks, but then you’re opting out and then you’re not part of society and society is demanding that you participate. You can decide to not do that, but then you’re a different part of society.

But you end up in systems where your kids are going to school and they have to opt into certain things. Or you want to use the Oculus VR system, you have to have a Facebook account now. It’s just like, well, you don’t want to have VR, but you need to use it at school. Well, you don’t want a Facebook account, but you have to have a Facebook account, and now suddenly it’s a Facebook thing. And then you’re down a rabbit hole, right? So, I think I look at it that way, if a country or group of people decide they want to do something and they want an AI or algorithms to make things more efficient, sounds good. But when people don’t have that choice, I think that’s a problem, and they really don’t at the moment.

Myrna (20:30): Yes. I agree. It takes away our individual sovereignty, the basic choices of how to live our lives and it creates separation. And you’re right, it’s playing out now in the healthcare system.

Seven: And you see this also now in things like GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). You can see GDPR is essentially a response to the kind of cultural hegemony of West Coast-based companies, right?

Myrna: Of course. With GDPR, Europe is trying to protect citizens’ data privacy.

Seven: Yes, lawmakers in Europe are saying, “hang on a second, we don’t have the same values as those companies. We don’t think that data should be collected in this way, even though you do.” California decided it wasn’t ok. You’re okay with it in general; U.S. law says it’s fine. But it’s actually rampant not just in Facebook, but rampant inside the credit system and you find that everything you do is being collected. We focus on Facebook and so on, but it’s really everywhere.

So in Europe, it’s different. Europe says, okay, fine. We’re going to let you do these things in some parts of the world, but we’re going to have laws about how you do them here. It’s a bit of a bandaid, right? It’s like, well, I’m still using the system, but now it kind of works, but maybe it doesn’t work quite as well. So now I have the second-degree version of Facebook, or I have Facebook that claims it’s not tracking me, but maybe it is. Maybe someone else is tracking that, I don’t even know what’s going on.

I’m a big fan of having more companies, more applications, more choices, and having the data, for example, be more decentralized. Why is it only Facebook that can access my Facebook social graph? Why can’t other companies access the Facebook social graph? I like the Facebook social graph, I like the connections I’ve built on that, but I won’t load Facebook anymore. I won’t load it on my computer because it feels like I like infected my computer with a virus.

I just don’t want to have to go through and reformat my hard drive. I mean, maybe I’m being sort of paranoid here. I can use a browser, I can block things, lots of tools like that for reference. But I just don’t want to do it anymore. Because I know that Google and Facebook, especially, have the best teams in the world to do ad tech and tracking. They’re just stellar. And so, I assume that if I connect from the wrong IP or something to identify me, that’s just logged and now forever, I’m tracked.

Myrna: You know too much.

Regarding AI and discrimination, I don’t know if you’ve seen the documentary The Coded Bias. That’s what that show is about. And discrimination, how they misidentify so many different types of people, so that’s important. Did you say that part of this discrimination problem and what you’ve experienced even just because of your accent, part of the algorithm is predicting what class people are in, right? What socioeconomic level they are?

Seven: Yeah, that’s a common thing in the UK. At Orchid, we’re a supporter of lots of particular kinds of values, which you can find on our websites. We’re very conscious of the human rights violations and discriminations that happen as a result of people’s color. I grew up in a fairly multicultural environment. Many of my friends at school were Indian origin or Pakistani origin or West Indian origin. So, it was sort of like color was normal. Obviously, there were a lot of white kids, but it wasn’t like a bubble of whiteness, right. The big discrimination, however, was what you sounded like.

It’s kind of strange to people in the U.S. because it’s just a sort of melting pot of accents. From what I understand, I mean, I wasn’t born there, but spent a long time there, but there isn’t an instinct that when you hear somebody speak a certain way, you automatically label them. Whereas in the U.K., because the queen speaks a certain way and because before her, the people who had more money and more guns were Royal, they had a certain way of speaking in the court. And at one point it was actually French that was supposed to be spoken in the court, the lingua franca.

But the language spoken in the court was proper English. The language that the Cockney guy, who was from London or East End, he’s not proper, he’s rough. And if you’re from Manchester, you talk like this. I remember my parents living there, where it was working class in coal mines and so on. And so, we still in English culture identify people subconsciously based on the way they speak. The BBC, for example, has gone to great lengths to house people with Welsh accents and other accents presenting the news. It’s no longer only the Queen’s English that you hear spoken on the BBC anymore, but it’s still there. And it’s still a tool.

Myrna: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Seven: In the words of Edward Snowden, who spoke at our recent conference, “Don’t stay safe, stay free.”

Myrna: Thank you so much, Seven. I really appreciate your time. This is very important work, so keep at it, okay?

Seven: Yeah. And just for reference, you can access everything about Orchid at orchid.com – just like the flower, and all our links are there. We’re happy to get in touch. Check out our apps and our mission. You can find me on Twitter.

Myrna: I also want to mention your YouTube channel, which is amazing with so many clips from your recent conference with Edward Snowden and other people.

Seven: Thank you.