Despite what is typically portrayed in the mainstream media, UAS are currently being used for a wide variety of civilian purposes and more applications seem to be discovered or invented all the time. The potential for UAS to provide geo- spatial tools for building a more sustainable world seem endless. In this issue, we highlight some of the companies focusing on these “UAS for good” services and the challenges they face, which include the regulatory sphere as well as fighting the negative image of “drones.”

Black Swift Technologies is all about building UAS for the everyday user. Their business focuses on intuitive, user-friendly, automated systems that can collect data for a wide range of end users, be they farmers or firefighters. Founded in 2011 by three University of Colorado PhD students, Black Swift has developed rapidly.

The company can now boast about a recently-secured NASA contract for developing an unmanned aircraft to map soil moisture, which will be the first of its kind. This project will build off of a NASA prototype used to assist evacuations during the flash floods that devastated Texas a few years ago. That prototype weighed hundreds of pounds; understandably it was not a system that was easy to use or fly, but Black Swift intends to change that. Together with their partners at CU’s Center for Environmental Technology (CUCET), Black Swift has developed a one to two pound version of the sensor and expects the system to be commercially marketable in two years. Not only will this system be able to make flash flood evacuations more efficient, which will be so valuable in situations like the recent Colorado floods, but it could also be used for a range of agricultural applications, improving farming practices anywhere.

What makes Black Swift Technologies particularly exciting is that they intend to offer these types of UAS to the average, everyday user. Their customers will need very little, if any, training to operate Black Swift UAS. As a result, they should be able to collect data easily and affordably, improving and even saving lives.

The Black Swift system takes off autonomously and lands itself. Some can even fit into a briefcase. This will make the Black Swift system optimal for use in high-stress and time-sensitive scenarios such as fighting wildfires or in search and rescue operations. In fact, the founders of the company are particularly passionate about this application. As avid backcountry skiers and hikers, they were fundamentally motivated by the potential for UAS to improve search and rescue efforts dramatically. FIGURE 1. Black Swift Technologies is not the only company currently examining the potential for drones to improve lives and benefit people in everyday life. Rocketship Systems is in the business of building user-defined, customized “robots that fly” for all applications except armed robotics. This was both a philosophical and business decision. Rocketship Systems believes that the future and value of UAS truly lies in these human and environmental security applications, not in the military or wartime purposes they serve so frequently today. Figure 2. Rocketship’s contribution to the future of UAS lies in creating small, user-driven designs. Counterintuitively, Rocketship Systems plans to provide customers with tailored systems that are more affordable than any mass-produced option available. For Rocketship Systems, the negative image associated with UAS is an educational issue. An important conversation needs to take place in the public sphere in the United States about the many civilian applications and potential for good that drones can offer. Black Swift co-founder Brad Cheetham agrees, as UAS applications continue to benefit people. “This will speak for itself when we’re able to deploy these systems.” Unfortunately, there are some regulatory obstacles in the way of that happening. Currently, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), responsible for overseeing UAS in the United States, only certifies UAS for a very restricted group of users, primarily government and academia. This severely limits the work that can be done to showcase the benefits associated with civilian UAS. In Europe, where such regulations do not slow down civilian UAS use, companies like the Swiss- based senseFly have designed and are manufacturing lightweight drones for civilian applications such as two-dimensional orthomosaics and three- dimensional elevation models that plug easily into GIS or agricultural software. When asked about the impact that the negative image of drones has on their business, senseFly indicated that this is really a U.S.-specific problem. “More and more people understand now the social benefits of civil UAVs, especially because they are used in many countries around the globe (Europe, Australia, South America, Canada),” said Baptiste Tripard, senseFly’s North American Sales Manager. senseFly has also been involved in and sponsors Drone Adventures, a Swiss non-profit that works to demonstrate the “many great applications of drones in conservation, cultural, humanitarian and search and rescue domains.” Until FAA regulations are updated to facilitate greater use of UAS for civilian applications, U.S. companies like Black Swift Technologies and Rocketship Systems must find ways to work within these restrictions. Black Swift Technologies works very closely with the FAA to secure certifications for all of their flights. Rocketship Systems keeps itself in business through its Flying Foam venture that sells components and kits for primarily recreational uses. Both companies are well-positioned in Colorado, where Senator Udall is working hard on legislation to update the current laws regulating UAS. With a combination of legislative review and the entrepreneurial spirit of companies like those highlighted in this article, drones may be getting a public image makeover very soon. Footnotes: 1. http://www.nationalturk.com/en/400-civilians-killed-in-us-drone-strikes-in-pakistan-in-9-yrs-42079

In Europe, companies like the Swiss-based senseFly have designed and are manufacturing lightweight drones for civilian applications such as two-dimensional orthomosaics and three-dimensional elevation models that plug easily into GIS or agricultural software. (This is not yet legal in the U.S.)

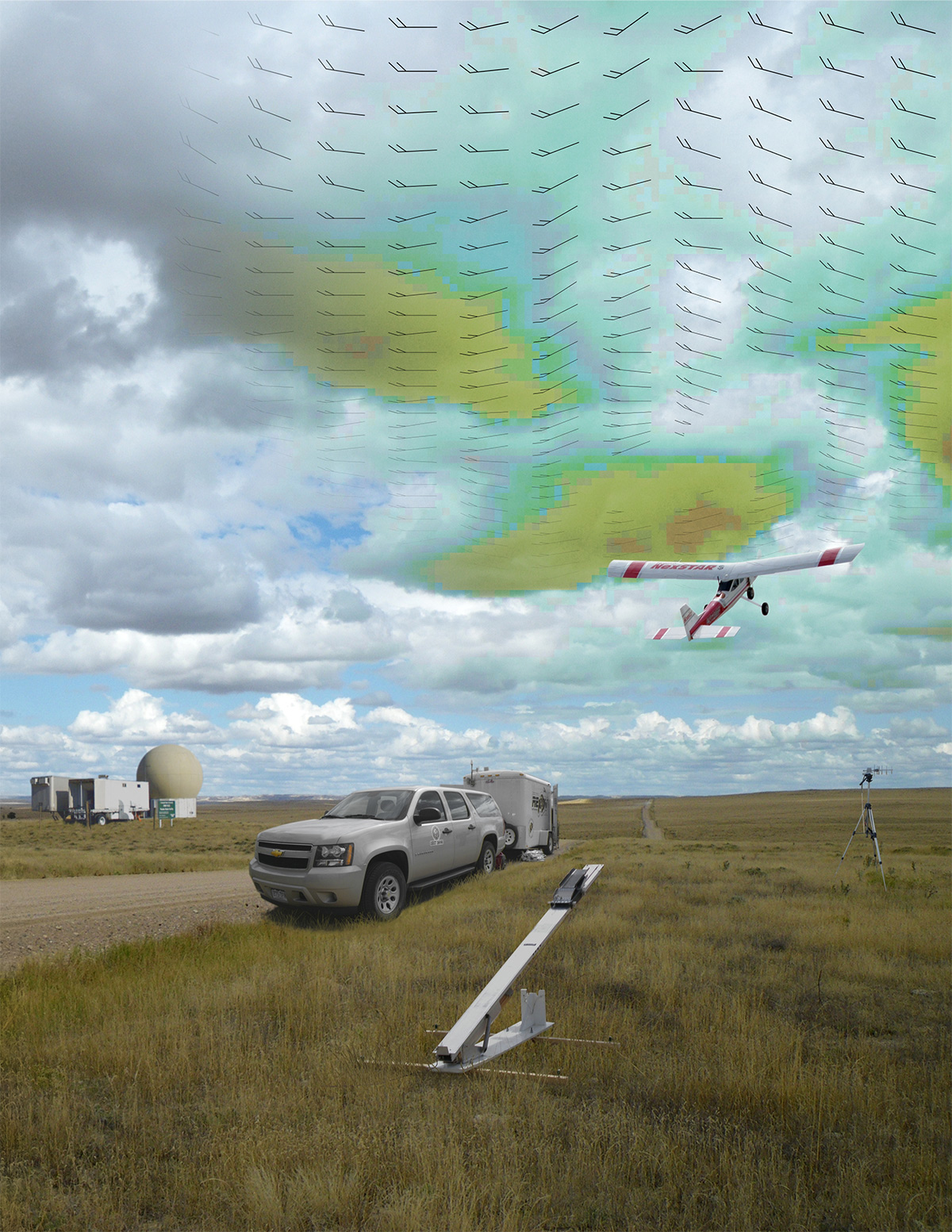

This image was created to demonstrate the meteorological utility of UAS ©2012 Jack Elston University of Colorado. Courtesy of Black Swift Technologies.

A shot during a test flight over a cornfield. ©2010 Jack Elston University of Colorado, courtesy of Black Swift Technologies.