BY MATTEO LUCCIO / CONTRIBUTOR

PALE BLUE DOT LLC / PORTLAND, ORE.

www.palebluedotllc.com

In May 2015, former slave fisherman Myint Naing, 40, was reunited with his family after 22 years. He was among hundreds of former slave fishermen who returned to Myanmar following an Associated Press (AP) investigation into the use of forced labor in Southeast Asia’s seafood industry. The persistent, meticulous, and sophisticated investigation by a team led by Martha Mendoza traced slave-produced seafood from Asia to major U.S. supermarkets, restaurants, and food suppliers, and resulted in the freeing of 2,000 slaves. This spring, the project earned the 170-year-old news agency its first Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, Mendoza’s second Pulitzer Prize.

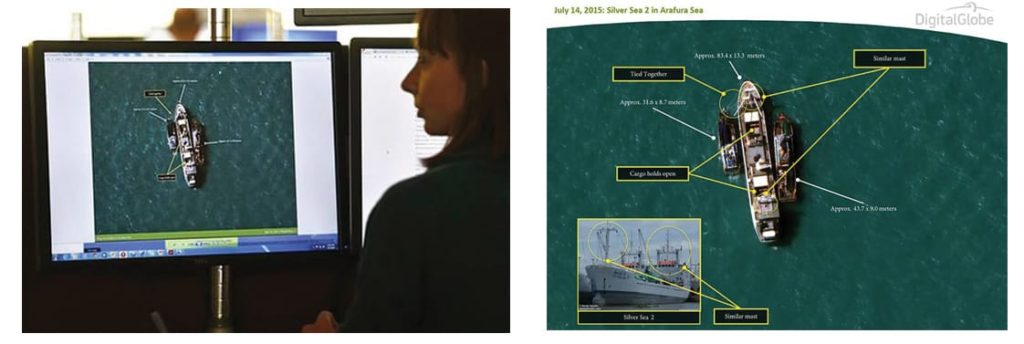

A key piece of the reporting was a stunning image captured by DigitalGlobe’s WorldView-3 satellite of a slave boat transferring its catch to a commercial fishing vessel in the middle of the ocean. An escaped slave corroborated that the boat was the one on which he had been forced to work.

THE COLLABORATION

DigitalGlobe often helps media organizations tell important stories about global events by providing them satellite imagery. “This AP story was the most shining recent example of the power of satellite imagery and geospatial information at work,” says Turner Brinton, DigitalGlobe’s Public Relations Senior Manager. The catalyst for this collaboration between DigitalGlobe and the AP was a phone call last spring from Mendoza about this project, on which her team had been working for more than a year. “The more we learned about what they were trying to do, the more we knew that we wanted to help and that there was a good chance that we would be able to do so,” says Brinton.

Mendoza was looking for large commercial fishing vessels that had been meeting up with slave boats where no one could see them and they could not be found. They would turn off their Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracking devices while they were doing this to prevent their locations from being known. This allowed the slave boats to transfer their catch to the commercial fishing ships.

The ships, in turn, would give the boats just enough food and water to keep the slaves strong enough to do their grueling work for 20 to 22 hours a day and stay out at sea for years at a time. “We’ve heard reports of these slave boats being at sea for five to ten years,” says Brinton. “These people were often captured from their homes and families or tricked into working on these boats. This is a textbook definition of modern-day slavery.”

Everyone at DigitalGlobe relies on its motto, “seeing a better world,” in making day-to-day decisions, says Nancy Coleman, the company’s Senior Director of Communications. Therefore, she recalls, when Mendoza called, she and Brinton felt empowered to decide to support the AP as part of their role as storytellers and in order to demonstrate what the geospatial industry can do. “Because we knew that this was in alignment with our purpose, we did not have to reflect on whether or not this had potential as a commercial opportunity,” says Coleman. “It was just the right thing to do.” She and Brinton have been fielding more investigative types of requests since and are exploring some currently. “We are extremely proud of our small contribution to this tremendous work that the AP has done,” says Brinton.

While this practice had persisted for generations and was well known, the image provoked a visceral response, and gave the Indonesian authorities the confidence to decide to intervene.

CAPTURING THE IMAGE

The AP team’s reporting led to the suspected location of the transfer of catch on the high seas. “A couple of months after our initial conversations,” Brinton recalls, “we received a call out of the blue one day.” The team suspected where a commercial fishing vessel was and needed to know whether DigitalGlobe could take an image of it. As it turned out, DigitalGlobe’s most capable satellite, WorldView-3, was within viewing distance of the area when the AP provided the coordinates. “We were able to take an image that same day and provide it to the AP with some analysis of what that image was showing, less than 24 hours after we received those coordinates,” says Brinton.

THE “SMOKING GUN” IMAGE:

This image of smaller illegal fishing vessels and a larger commercial vessel, the Silver Sea 2, a Thailand-owned refrigerated cargo ship, in the Arafura Sea south of Papua New Guinea, led to the eventual release of about 2000 forced-labor slaves. DigitalGlobe imagery analyst Micah Farfour is shown here. Images courtesy of DigitalGlobe.

The AP team knew specifically which ship they were trying to catch in the act because they had people on the ground, Coleman explains. “They had ground truth and photographs of the ship they were looking for. Their reporting ultimately led them to observe the suspected fishing ship at port and correlate its tracking signal. When it left port for one of the suspected slave boat rendezvous, AP provided the approximate latitude and longitude for where the ship was headed just before it turned off its tracking signal. Despite this, it was still a needle in a haystack problem, as the ship could have been anywhere within a 500-square-mile area.

The series of AP stories was the catalyst for a lot of action, (including) freeing more than 2,000 men from fishing boats.

Ultimately, one of the first people who saw the satellite image we provided was an escaped slave who was able to confirm that it was indeed the ship from which he had escaped.”

“Only a satellite like WorldView-3, with its large aperture and sophisticated pointing agility, could have captured the right image at the right time,” says Brinton. “The 30-cm satellite image enabled a positive identification of the commercial fishing ship, showing its cargo holds open to accept the slavecaught fish.”

This spring, the project earned the 170-year-old news agency (AP) its first Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

THE CONSEQUENCES

DigitalGlobe provided the image to the AP, who, in turn, provided it to the Indonesian authorities. “They did so much ground work that they already had contacts in the government who were aware of this issue and the AP’s investigation,” says Coleman. “The imagery that we provided was the smoking gun that allowed the authorities to intercept the vessel, arrest the captain, and free the men onboard.” While this practice had persisted for generations and was well known, the image provoked “a visceral response,” says Coleman, and gave the Indonesian authorities the confidence to decide to intervene.

The series of AP stories on this subject, collectively titled “Seafood from Slaves,” came out last summer and fall and was the catalyst for a lot of action that has happened since, in addition to leading to the freeing of more than 2,000 men from fishing boats. It led to legislation signed by President Obama that closed a loophole in U.S. law that allowed for goods produced by slaves to be sold in the United States, and demands for change by U.S. importers have resulted in three class-action lawsuits.