EXECUTIVE INTERVIEW

Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky, is a composer, multimedia artist, and writer whose work immerses audiences in a blend of genres, global culture, and environmental and social issues. Miller has collaborated with an array of recording artists, including Metallica, Chuck D, Steve Reich, and Yoko Ono. His 2018 album, DJ Spooky Presents: Phantom Dancehall, debuted at #3 on Billboard Reggae.

His large-scale, multimedia performance pieces include ìRebirth of a Nation;î Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica, commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music; and Seoul Counterpoint, written during his 2014 residency at Seoul Institute of the Arts. His multimedia project Sonic Web premiered at San Franciscoís Internet Archive in 2019.

He is currently the inaugural Artist-in-Residence at Google Arts & Culture. He was the inaugural Artist-in-Residency at the Metropolitan Museum of Artís The Met Reframed, 2012-2013. In 2014, he was named National Geographic Emerging Explorer.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Paul, I am really excited to speak with you today. Thank you so much for joining us.

PAUL MILLER: Hey, it’s a pleasure. Beautiful day here in New York.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: And in Denver as well. I think one thing I’d like discuss is the urgency of what’s happening with the climate, because in the end if we don’t take serious action, we, humanity, won’t have a place to live. One way to reach people with this message is with music and art.

So that’s where you come in. Can you introduce yourself? Some of our readers may not be aware of who you are.

PAUL MILLER: Sure. Well first of all, I’m Paul Miller. That’s my real name, and then my performer name is DJ Spooky. That’s D as in ‘digital’ and J as in ‘join.’ I’m from Washington, D.C. I went to Bowdoin College in Maine. My degrees are in philosophy and French literature. Both my parents were professors. I grew up in a household that very much valued information. So it’s a situation where you find yourself in 2019 – there have been so many evolutions of how people look at art or data or what I now call “data-driven aesthetics.” Now, it’s its own world at this point. That’s where DJ culture and the arts connect. It’s all about pattern recognition.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Right. That’s great. I’ve really just been realizing the past few years how important art and music are in the whole conversation of the changing planet. I’ve been publishing Apogeo Spatial for 16 years, and I have really focused on the science, which is of course very important as well.

PAUL MILLER: Right.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: So music and art help to bridge the gaps that are out there and they also open people’s hearts, which changes the perception of what you’re talking about. I’m really working on this wake-up call for humanity so we can all change what we can do in our lives to have a future; I think that there are a lot of things that you are doing that speak directly to that. Do you want to share anything about any of your particular projects?

PAUL MILLER: Sure. 2019 is a strange year. On one hand, it’s the 30th anniversary of the web. So Tim Berners-Lee wrote the first source code for the web as we know it in 1989. But ARPANET, as we know it, started in 1969. So it’s the 50th anniversary of the internet and the 30th anniversary of the web.

My current project I’m doing is called Quantopia – it’s quantified utopia. It’s done with a sense of humor – the landscape and a culture made of numbers. It’s about how we look at data- driven society especially with the way networks such as the internet or web has transformed culture. Now you can buy any medications on the Internet and get them in your care the next day. That’s my current, it’s a music composition that looks at what I call “the acoustic portrait of the entire internet.” When you think about Quantopia, look at composers like John Cage on one hand, or scientists like Galileo, or Johannes Kepler, all of whom were inspirations for me.

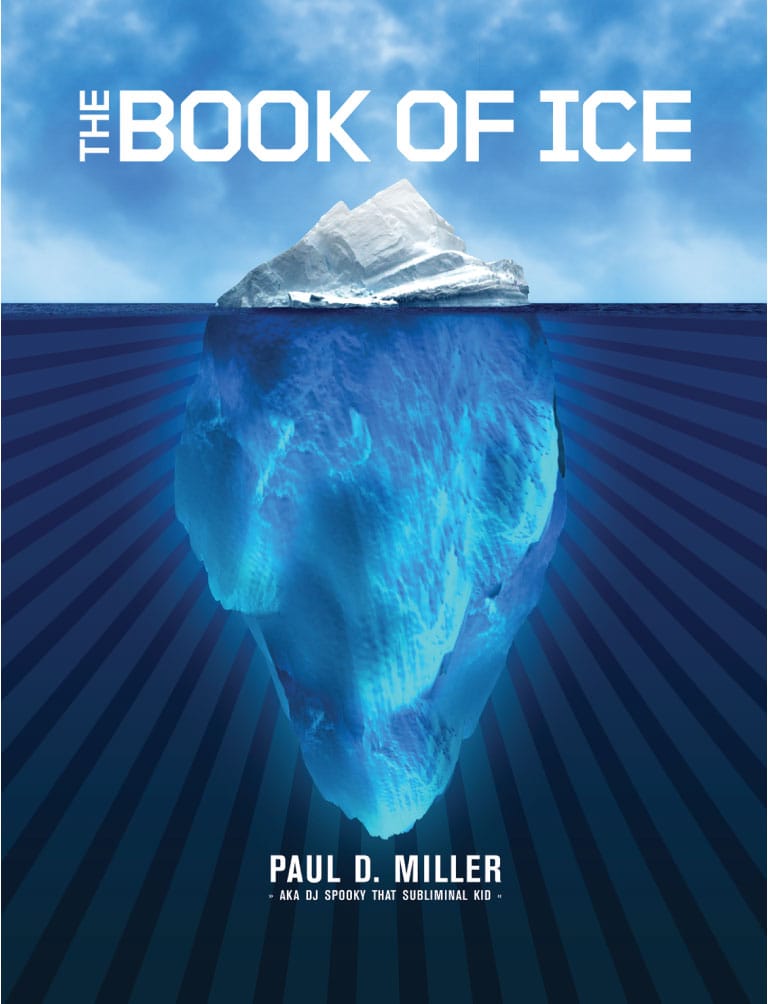

TerraNova: The Melting of

Ice in Antarctica

PAUL MILLER: There’s another project which is called The Science of Terra Nova, and it’s a project where I went to Antarctica for several weeks, and wrote a massive music composition based on looking at the geometry of ice.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: That’s really great. One of the most important things that you do is put music to things that people wouldn’t expect. You literally were listening to the ice, and putting music to the melting of the ice to make a point, right?

What was involved with the project?

PAUL MILLER: It’s a multimedia project. I’m more into interdisciplinary, and so film is a component and it’s composing, it’s performance art and things like that. This one went to the Met (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) in New York, the American Museum of Natural History, and it traveled to a whole bunch of museums throughout the country, and Europe as well. These are all projects that travel and score as concerts, so they’re film, they become books, and so on and so on.

(Editor’s Note: The presentation that traveled to museums is called Terra Nova: Sinfonia Antarctica. In order to understand better the fragile environment and ecosystem of Antarctica, Paul traveled to the continent with a mobile recording studio in order to capture sounds of ice and the reverberations it produces.)

MYRNA JAMES YOO: I see. So you do your projects as multimedia and they all have original compositions within them that you’ve written. In this Antarctica project, did you make the point about the melting ice as it relates to climate?

PAUL MILLER: Well, melting is a temperature differential that I applied to music. I’ll give you an example. Melting ice or freezing ice occurs at very specific temperatures, so even the geometry of ice would only come into play if there’s a certain temperature that triggers that phase transition.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: So it’s an indicator of what’s happening.

PAUL MILLER: Right, so what makes water become ice is just this small temperature differential on this sort of compact molecules, and stuff like that. It’s pretty amazing to see. I really enjoy seeing how these kind of phenomena make you realize that there’s mathematics in nature at every level.

You guys are focused on geospatial issues. One of my favorite ways for portraying that is called Ichnographic Representation. It’s basically an axonometric kind of representation that Leonardo da Vinci started around 1502. Many map makers looked at his first map of a fort in the city of Imola, Italy, as one of the first ways of thinking about satellite image representation.

That kind of stuff inspires me, the fact that before we had the silos separating math from philosophy or math from music, people just did what they did, they had to think about patterns. This is the 500th year of da Vinci’s death this year too, so we have the 50th year of the internet, and 500 years of da Vinci so, it’s a good year of anniversaries.

50th Anniversaries and the Significance of 1969

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Wow. It’s also the 50th anniversary of walking on the moon on July 20th, and 50 years ago, Jack Dangermond started his iconic GIS company, Esri.

PAUL MILLER: So in 1969 you had a man on the Moon, you had the internet, you had Woodstock, and you had the beginning of the industry that organizes all the geospatial data.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Culturally that’s just incredible isn’t it?

So back to da Vinci, that’s amazing that he was able to do accurate drawings of an aerial view, which we now take for granted, as we see photography from airplanes, and space and drones every day. He was so ahead of his time in so many ways. Incidentally, we have one of the biggest exhibitions of his work here in Denver right now at the Museum of Nature and Science, which is fantastic. He’s a hero of mine, and was a true Renaissance man.

PAUL MILLER: Oh I will check that out. I’ll be in Colorado next week.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: I love the idea of thinking about everything that was happening at once back then and that there’s something to be celebrated about these anniversaries.

The Importance of the Arts

PAUL MILLER: Well the thing that is the common denominator for all the things in 1969 – you have someone on the Moon, you have the internet, and you have Woodstock – is that these are where pop culture and technology have been a swirling cocktail of all sorts of different issues that led to us being more and more of an information-based society. Woodstock, one could argue, shattered so many of the norms and how people felt that sound could be represented, whether it be noise, or rock, or anything, all of which was technology-

MYRNA JAMES YOO: And also what it could mean, right? It has so much meaning for so many people.

PAUL MILLER: Yeah, so, there’s a lot to be said for how people and the arts can kind of be reflector sites for the sciences. I actually firmly believe that we need to make a more robust conversation between science and the arts, so that’s something I’m really interested in overall.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: It’s also interesting that it’s time yet again to break down silos, because everything is connected; everything affects everything else, in our lives and in the world. So, it’s an important conversation to have, and I think that’s one of the things that will help us leap-frog forward in understanding and communicating what’s really happening with the planet – with the Earth – is to break down more of those silos. You know, that’s one reason that your work is so important. It’s because you’re doing that and demonstrating, literally, how everything is connected.

PAUL MILLER: Right. Thank you, I really appreciate that. My motto these days is all about pattern recognition and we have to really think of different approaches to how the arts can give people different patterns; that’s the point.

So, when you’re talking about geospatial issues, the Cold War is what really set up much of the issues that we are thinking about today with satellites. So in 1957 was the first launch of the Sputnik from Russia and the Explorer satellite went up soon after.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Yeah, we had the great competitive “Space Race” with the Russians and now of course we’re collaborative with the Russians at the space station, which is an important thing.

PAUL MILLER: I’m just saying that the legacy of those satellites that were put into orbit actually created a whole different perspective that still ties back to Leonardo da Vinci, because he was the first artist to think about satellite representation before there were satellites. He drew these kinds of maps in 1502 that look exactly like Google Maps, but at that time nobody had that sense of perspective.

A lot of people are very intrigued by his history of map making, but every cell phone that you have, everyone on the planet, amusingly enough, we’re still dealing with the geospatial cold war. The legacy of that is in mobile media in a lot of different levels – whether it be 4G LTE that was invented during World War II, or at least the precursor to it, and so on.

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Right. Is there anything else in particular you’d like to share or talk about?

PAUL MILLER: Yeah, so when you look at hip-hop, or techno, or dubstep, or any of the major forms of music that are going right now, they’re all based on quantized rhythms, usually 4/4 tempo and the variation in tempo. Techno is a little faster than hip-hop, hip-hop is a little slower than other styles, and dubstep is a little slower than that.

To me these are all really fascinating ways of human beings organizing experience, and putting a tempo or rhythm to it, and that’s what’s beautiful about math is that we understand those differentials and can actually use them to generate music. That’s part of my compositional approach, that I use math as a component, but it still should be reasonably accessible. That’s what I just wanted to wrap it up with.

“Melting is a temperature differential that I applied to music. I’ll give you an example. Melting ice or freezing ice occurs at very specific temperatures, so even the geometry of ice would only come into play if there’s a certain temperature that triggers that phase transition.”

MYRNA JAMES YOO: Oh that’s really great. I just met a mother whose son has autism and he’s a music savant – you know a lot of autistic people have something they’re very, very good at – and he did not understand math at all. Then when he was about 15 years old, he was playing the saxophone, when he really learned the music, and the math just clicked in. I think this verifies what you’re saying – that math is underlying all of those types of things; it brings us back to everything being connected, doesn’t it?

Thank you so much! This was really great.

PAUL MILLER: Excellent, thanks.

Art in Space

Artist Trevor Paglen’s

Satellite-as-Art

Artist Trevor Paglen’s art installation “Orbital Reflector,” is “installed” in space, but has not been activated, waiting for clearance from the federal government. Trevor is an American artist, geographer, and author whose work tackles mass surveillance and data collection. This particular piece of art is a 30-metre-long reflective, diamond- shaped balloon made from a material similar to Mylar – a form of plastic sheet made from polyester resin. A brick-sized smallsat containing the inflatable artwork was launched into Earth’s low orbit on December 3, 2018 as part of a SpaceX launch on a Falcon 9 rocket with 64 satellites.

Humanity Star

Humanity Star, the first satellite launched purely as art, was launched in January 2018, and plunged back to Earth only two months later. It was launched by Rocket Lab’s Peter Beck. It was a highly reflective “disco ball” satellite, designed to be seen from Earth.