BY LINDA DUFFY / PRESIDENT / APROPOS RESEARCH

GOLDEN, COLORADO / WWW.APROPOSRESEARCH.COM

REMOTE SENSING, AERIAL IMAGING, LIDAR and other technologies allow us to map almost every inch of the Earth with unprecedented precision. This approach supports in-depth geospatial analysis based on quantifiable data; however, there is great value in adding qualitative information to the mix.

By incorporating factors such as cultural practices, traditional tribal boundaries, and public sentiment into our maps, decision makers can make better choices about resource management, urban development and overall land use. The current trend towards participatory GIS (PGIS) is tapping into the invisible data possessed by people living in communities who previously had difficulty being heard on issues that impacted their quality of life due to their lack of official status and authority

INVISIBLE DATA

Dr. Melinda Laituri, professor of geography at Colorado State University, discussed the value of collecting invisible data using participatory GIS (PGIS) in her keynote speech at the 2015 GIS in the Rockies conference. Dr. Laituri has worked with indigenous people around the world to create maps that integrate spatial and non-spatial data to provide better tools for decision making, and ultimately help marginalized groups.

“Development projects are driven by community needs and issues,” explained Laituri. “In addition to non- crisis mapping to support land use and resource management, the value of accurate maps has been proven repeatedly in emergency response and in rebuilding after natural disasters.But not only do we need anaccurate record of roads, population centers, and hospitals; we need to identify cultural practices and other invisible factors that are not normally mapped and include these in the analyses to make the best decisions.”

PARTICIPATORY GIS

PGIS is sometimes referred to as collaborative mapping, volunteered geographic information (VGI), or crowdsourced mapping; the basic idea is that members of a community possess knowledge not known by outside parties, and that locals should have the opportunity to create their own maps, or augment existing maps, that include information important to them.

In developed countries, this sharing of information may take place at a mapping party where volunteers get together to contribute points of interest to a city street map. In developing countries, it more likely involves donations of hardware and software and grants to support teams of researchers who educate local people about the use of geographic information and to help them build maps from scratch. Increasingly, bridges are being built between off-site and local mappers to integrate tools, technologies and spatial information about places that lack geospatial information.

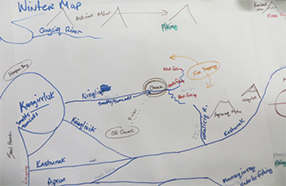

FIGURE 1. Participatory map of subsistence practices, Yukon River Delta, Alaska. Courtesy of M. Laituri.

“I’ve worked with marginal populations around the world who have not been heard and have not been able to map in the past,” said Laituri. “The issues being addressed depend on the location. Some people are dealing with climate change that leads to new migration patterns of traditional food sources, or coastal flooding that threatens existing towns and villages, or invasive species pushing out indigenous plants.”

APPLICATIONS OF PGIS

Awareness of the value of geographic information provided by volunteers has grown over the past fifteen years following a string of natural disasters, including the devastating earthquake in Gujarat, India, in 2001; the tsunami in Indonesia in 2004; Hurricane Katrina along the U.S. Gulf Coast in 2005; the earthquake in Haiti in 2010; and the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa in 2014.

During these events, the Internet made it much easier for volunteers to contribute time and money without actually traveling to the impacted site, while consortiums of international agencies and commercial entities joined forces to make technology and tools available. In some cases where government agencies were overwhelmed, NGOs and private individuals contributed a great deal, such as the “people finders” website created by individuals after Hurricane Katrina, and maps of Haitian refugee camps developed by volunteers on OpenStreetMap. Invisible data also helped prevent the spread of Ebola in West Africa after cultural data about kinship networks and burial practices were analyzed.

FIGURE 2 .Remote locations increasingly have connectivity through innovative use of technology. This shows a Mongolian household. Courtesy of M. Laituri.

Applications of maps created using PGIS include urban planning, infrastructure planning, health studies, irrigation and drainage, social and economic planning, land tenure, and disaster mitigation. “One of the biggest challenges we have with PGIS is to facilitate actions afterward without inflicting our own values or opinions on a community,” said Laituri. “We can educate local people about GIS and provide them with satellite images, GPS units and other equipment, but ideally we would like to revisit and make sure that the maps are continuing to address the community issues and successfully empowering the people.”

ENVIRONMENTAL PGIS

In North America, community-based mapping got its start in the ‘90s when university students with access to computers and GIS software worked with grassroots organizations to analyze the impact of activities that could harm the environment, such as mining, drilling and logging. Dr. Renee Sieber, associate professor of geography at McGill University and Chair of GIScience 2016, began her career as a community organizer, during which time she observed the use of maps made by third parties that didn’t necessarily reflect the whole truth about actual conditions. To counter the misleading representations, she and her co-workers began making their own maps.

“Back in the 1990’s, the technology was difficult to work with,” Sieber said. “But I really believed that com- munities should make their own maps and not wait for someone else who probably didn’t have firsthand knowledge of the issues in the area.”

“There are really two types of participatory GIS,” Sieber continued. “PGIS has more of a community mapping focus, and includes drawing a map in the dirt with a stick, as well as marking points on a contour map on a tablet. PPGIS is public participation GIS, which involves more advanced spatial analysis and commonly takes place throughout North America, rather than in developing countries.”

Sieber points to environmental grassroots organizations operating on a shoestring as an example of cre- ating maps without expensive software and hardware, and successfully communicating vital information. “Counter-maps offer a bottom-up perspective from the local people, as opposed to a top-down perspective from government authorities or industrial representatives,” Sieber explained. “Counter-maps had a huge impact on legislation related to logging old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest, with habitat protection for spotted owls being one of the most contentious topics. And in developing countries, community-generated maps have been a valuable tool for indigenous groups to protect their property from exploitation.”

WHO IS HELPING?

There are many entities involved with PGIS today. Some NGOs, such as Ecocity Builders, and founda- tions, such as Secure World Foundation, focus on educating local groups about GIS and how to use the tools available to build healthier urban environments. The Association of American Geographers also participates in research and education projects worldwide to spread knowledge about mapping and its diverse applications, while industry representatives, such as Hewlett Packard and Esri, donate hardware, software and expertise to assist mapping projects.

Regional groups like Kathmandu Living Labs concentrate their efforts on helping their own communities to improve everyday life, as well as responding to natural disasters. As covered in this publication previously, Ushahidi has developed an open source tool for collecting crowdsourced input from multiple sources (smart phones apps, email, Twitter), filtering and managing the data, and creating user-friendly visualizations in the form of maps and charts.

FIGURE 3. Participatory mapping in the Bale Mountains of Ethiopia using satellite imagery and local experts. Courtesy of M. Laituri.

Since being founded in 2006, OpenStreetMap has recruited volunteers on a global scale to contribute to a map of the world that is not subject to licensing fees. The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) supports the use of open source and open data sharing for humanitarian response and economic development and was active in Nepal after the 2015 earthquake.

SPATIAL AWARENESS IN THE FUTURE

All kinds of information related to location, geography and people is important to support decision making. This realization is driving the development of creative ways to collect and utilize data. Dr. Laituri believes, “PGIS and the increasing availability of online tools and collaborative mapping efforts raise the visibility of not only invisible data, but also spatial thinking and its relevance in everyday life.”

“The future looks very bright for community-based mapping,” said Sieber. “We will see more analytical tools and more projection libraries available on the GeoWeb, and advanced use of social media to create sentiment analysis maps representing community feelings. There will be more MapTime groups that offer tutorials to edu- cate their members about GIS and mapping, and growth in the number of volunteer organizations who are dedicated to mapping the world. There is a lot happening on many fronts.” The magnitude of the full impact will likely exceed our imaginations.